SETTING THE PACE: A DROMOLOGY OF SHAKESPEARE TRANSLATION IN POST-WAR JAPAN

Abstract

Pace is important to Shakespeare translation as a means of reproducing the dramatic integrity of the original plays and of maintaining audience interest. By the time that Fukuda Tsuneari came to translate Shakespeare in the 1950s, the plays had already been known in Japan for over seventy years, but had been staged mainly on an occasional, even experimental basis. Fukuda sought to bring Shakespeare’s works to a wider audience by imitating the dramaturgy he admired in English productions of his era, and believed as a translator with an interest in native language reform that the pace or action of the plays was innate to their language. This notion of pace coincides with Paul Virilio’s theory that speed helps spectators to perceive phenomena more easily, suggesting also – in an age of virtualization – the role of Shakespeare translation in setting realistic limits to the speed with which phenomena are generated and received.

Article

Fukuda Tsuneari (1912-94) started to translate Shakespeare in the early 1950s, shortly after the end of the American Occupation of Japan in 1952. Over the next thirty years, he was to translate some nineteen of Shakespeare’s plays; these were intended primarily for performance by the theatrical companies with which he was associated but also as reading texts by the Shinchosha publishing company, and although Fukuda’s translations are now seldom used in performance, the published editions remain popular. In order to understand Fukuda’s contribution to the history of Shakespeare translation and performance in Japan, it is probably best to start by placing him between Tsubouchi Shoyo’s pioneering translation of the Complete Works, published between 1909 and 1927, and the contemporary translations by Odashima Yushi from the 1970s and 1980s and Matsuoka Kazuko’s as yet incomplete translation of the Complete Works, initiated in 1997.

Tsubouchi’s translations are significant for a variety of reasons, but perhaps most of all – in their quest for a competent translation style – as a relativizing of differences and similarities between Shakespeare’s rhetoric and Tsubouchi’s own literary tradition through his tendency to juxtapose pre-modern and contemporary linguistic registers (1). Although this approach succeeds in foreignizing Shakespeare, its acceptability depends on a problematic assumption of continuity between Japan’s pre-modern and modern cultures. Tsubouchi’s view of Shakespeare as an essentially unknowable genius may have enabled Tsubouchi to erase these historical differences to his personal satisfaction, and it was a personal issue for him because Tsubouchi was a writer who straddled Japan’s feudal past and its modernity (2). For post-war translators like Fukuda, Shakespeare is set less ambiguously within the historical framework of Japanese modernity, especially that of the modern Japanese theatre (shingeki), and so the goal of Shakespeare translation becomes simply to release the power of Shakespeare’s realism within that framework (3).

Odashima also translated Shakespeare in the hindsight of considerable historical change, but that of the rapid economic growth of the 1960s and associated political unrest, when the challenge became to make Shakespeare relevant to the younger generation for whom Shakespeare was an authority figure and who have had new material distractions of their own. By contrast, Fukuda stands out from Tsubouchi and Odashima in being more purely interested in the dramatic potential of Shakespeare’s language; the reason why he never translated the whole of Shakespeare, unlike the other two, is that Shakespeare translation was only part of his broader dramatic agenda, since he also wrote voluminously on the theatre, translated the plays of Oscar Wilde, and wrote several plays of his own. Furthermore, while Tsubouchi’s quest for a style of Shakespeare translation is typical of the pre-war trajectory to catch up with the West, and Odashima’s nativization typical of a newly rich and confident Japan, Fukuda’s dramatic realism seems grounded in the early post-war resignation to Western hegemony, which in Fukuda’s case led him to support the controversial ratification of the United States-Japan Security Treaty in 1960 (4).

Realism as a theatrical genre dates back to the late 19th century, and was received as such by the founders of modern Japanese drama in the early years of the 20th century through their translations of the plays of Henrik Ibsen. Dramatic realism has been subject to various interpretations (5). but for Fukuda it was a means of perceiving a reality other than his own: in other words, of recognizing a reality that originated in a mind and culture other than his own. For this reason, Fukuda tended to eschew efforts to Japanize or modernize Shakespeare – what at one point he calls ‘hippy Shakespeare’ (in Anzai, 223) (6) – and insisted that realism was not psychological drama (226).

Of course, Shakespeare can be very psychological, but overly psychological direction risks imposing on the Shakespearean text the modern Freudian assumptions of the 20th century. For Fukuda, Shakespeare’s reality is no more than ‘the development of the plot on stage and the changes in character and action’ (ibid.). Thus, his sense of realism flies in the face of post-shingeki directors like Ninagawa Yukio, who has repeatedly insisted that he must Japanize Shakespeare to some extent in order to make the plays accessible to Japanese audiences (Kawai, 272-3). Fukuda wants only that Shakespeare speak for Shakespeare, and he does so as a representative of the one generation in modern Japanese culture to have taken Western, especially Anglo-American culture, more seriously than any other generation, namely the early post-war generation of writers and intellectuals who had experienced the defeat of 1945 and were charged with the responsibility of revitalizing the culture (7).

Japan’s defeat was symbolized by Emperor Hirohito’s renunciation of his divine status in the Japanese Constitution in 1947, although it was his famous ‘Jewel Voice Broadcast’ of 15th August, 1945, when he went on radio to announce the Japanese military surrender, that can be said to represent the more dramatic break with the past (8). Prior to that speech, the majority of Japanese people had never heard the Emperor’s voice; under the previous Meiji Constitution promulgated in 1889, all Japanese discourse had in a sense been directed towards the Emperor’s silent but benevolent presence at the heart of the national polity (9). Thus, Hirohito’s unexpected intervention in the sphere of Japanese discourse was bound to affect the language’s parameters and conventions.

Some immediate reforms that followed included the simplification of the writing system, the abandonment of most of the honorifics used for referring to the Emperor’s person, and the introduction of English as a compulsory subject in Japanese schools, but a more radical change in a post-imperial society where linguistic exchanges were no longer governed by the framework of the national polity but resided in the democratic sovereignty of the people was a liberating awareness of the power of language to effect change. Fukuda himself took a conservative attitude to language change, believing that it was not the script that had hampered communication but the conflicting goals of nationalism and westernization (Fukuda 1988, 338); like several of his contemporaries, he continued to use the unreformed script well into the 1970s. Yet Fukuda’s awareness of the innate power of language is undoubtedly democratic, and a recurrent characteristic of his Fukuda’s dramaturgy, as he explains in a discussion of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, where he argues that language (gengo

or kotoba) is inherently active (kodo).

The notion that language is action is much more noticeable in drama that it is even in the novel. Not only in Antony’s oration but in all great drama, and especially in Shakespearean drama, language is all action. We tend mistakenly to assume that language is somehow or other the expression of feelings and action the movement of arms and legs, but that is not in fact the case. To give a trite example from everyday life, the phrase ‘Open the door’ will cause either the speaker to open the door if there is no one inside, or if there is someone there, and even if that person happens to be one of your parents, to cause the other person to open the door on the speaker’s behalf. Even at this rather basic level, language always serves to bring about action, indirectly, and we use language to function as an extension of our arms and legs in place of using our arms and legs. Language is a tool just as our arms and legs are. That is a trite example, as I said, but in the world of drama, especially of a great playwright like Shakespeare, language may be made to behave in an even more active manner.

(Akutagawa, 150-1)

What Fukuda is arguing towards is a drama of language in which things happen because people say that they will happen, and where drama is real because language is the main medium out of which reality is constructed.

One of Fukuda’s purposes in translating Shakespeare was undoubtedly to give Japanese audiences the confidence to construct their reality, which had of course been shaken by the events of the war, and in this regard he suggests that the problem is not the language itself but rather Japanese people’s perceptions of their language, writing that

In Shakespeare, speech and language causes people to act in certain ways; linguistic assertions create new responsibilities. In an agglutinative language like Japanese (10), there may be several cases where the sense of assertion and responsibility is prioritized due to the way that sentences are inflected, or subtle emotional shifts and exclamations are heightened, and yet it is no easy task to generate the rhythms to which words give rise, those rhythms that drive the actions of characters through to the very end. I have never been one of those to believe that Japanese is an emotional, illogical language, and yet there are many Japanese people who want to believe that, which is a prejudice that logically can only serve to undermine the Japanese language. A linguistic proposition is a behavioural act, and as such can lead to mistakes. We have to take responsibility for our own behaviour. If we do not have the courage to release the active potential of words, then the feelings and exclamations they produce can appear as no more than false sentiment. We have to rid ourselves of our complacent prejudices. If we do so, then the translation of Shakespeare’s plays into Japanese becomes possible.

(Fukuda 1988, 338)

Fukuda’s polemic can be linked to J.L. Austin’s speech act theory and the existentialism of Heidegger and Sartre, both of which were influential among Japanese intellectuals in the 1950s and 60s; the reality of a writer like Shakespeare is glimpsed both comically and tragically in the success and failure of authentic speech acts.

Fukuda’s sense of the possibility of Shakespeare in Japanese was affirmed most significantly, however, through a visit he made to London in the spring of 1954, in particular a production he saw of Hamlet

at the Old Vic Theatre, directed by Michael Benthall, and starring Richard Burton as Hamlet and Claire Bloom as Ophelia. Some have said that Burton was ‘too strong’ in the role, but what impressed Fukuda most about the performance was its pace and vitality, far greater than anything he had ever seen in Japan (Fukuda 1988, 337-8). The Shakespeare productions Fukuda had seen in pre-war Japan were examples of what Peter Brook was later to call ‘deadly theatre’, namely little more than staged readings, whereas the Benthall production convinced him that purposeful, dramatically aware Shakespeare speaking was not only possible but could be readily translated onto the Japanese stage.

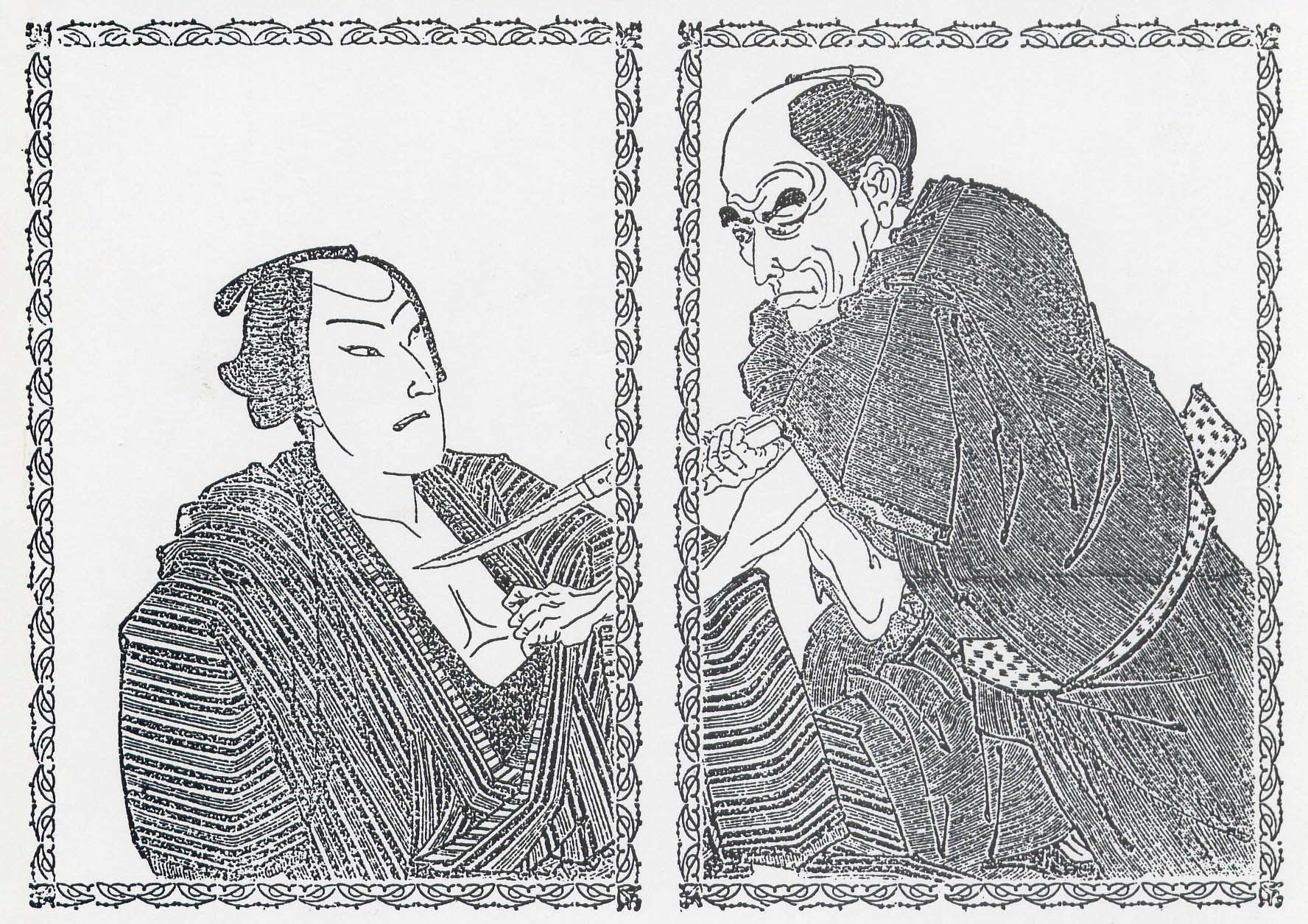

Shakespeare production up to that point had been dominated by the Tsubouchi translations. Tsubouchi was a connoisseur of kabuki, the traditional Japanese dramatic genre that originated in the 17th century, and so not surprisingly his Shakespeare translations are said to be influenced by kabuki. In fact, they are influenced more by Shakespeare than by kabuki, but when one considers that like other traditional Asian genres, kabuki is a relaxed and refined form of entertainment that takes at least four hours in performance, while the average Shakespeare production is more like three hours, and that the kabuki genre tends to emphasize dramatic highpoints and individual scenes above the overall dramaturgical structure and dénouement of plays, then it is only natural that Tsubouchi’s Shakespeare should have been perceived as ‘slow’ (11).

The original performances of Shakespeare’s plays over 400 years ago were also ‘slow’, but the point is that by the mid-20th century English had become a faster, more precise language, and the technology greatly extended; one of the demands of commercial theatre, for example, is that performances should be between two and three hours in order to fit in with the schedules of audience members. Fukuda’s response to the speed and pace of the Richard Burton Hamlet, therefore, was not necessarily one conditioned by the original text, although it was an appraisal of Shakespeare’s play as a series of speech acts.

As a basic illustration, we can compare the differing styles in which Fukuda and Tsubouchi translate Hamlet’s soliloquy, ‘To be, or not to be’. In this speech, Hamlet contemplates killing himself, faced as he is with the enormous task of avenging his father’s murder by killing his uncle. In 16th century Europe, suicide was a mortal sin, but for Hamlet the problem (or ‘rub’ as he puts it) is that suicide will take him into unknown and unknowable territory, whereas the choice to live allows him some control over his destiny, and since the killings he does perpetrate after this time are acts of self-defense, we can assume he chooses against eternal damnation.

For Fukuda, who was allegedly sympathetic towards Christian teaching, we can see how a choice is opened up between a decision to live and a retreat into false sentiment, whether through suicide or inaction. Hamlet chooses to obey the dictates of his father’s ghost and his own conscience, thereby allowing the words of vengeance to follow their natural logic and (in Fukuda’s terms) to generate the rhythms of the play; Hamlet’s soliloquy is also generally interpreted as being more than a speech about suicide, but also about action and commitment.

In traditional Japanese culture, suicide could be both honourable and courageous, but Fukuda is reading Shakespeare from the hindsight of both the modernization of Japanese culture after the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and of the manipulation of ‘honourable suicide’ as a strategic weapon during the period of militarism and war, but also from the hindsight of a number of suicides by well-known writers during the first half of the 20th century, such as Akutagawa Ryunosuke in 1927 and Dazai Osamu in 1948, who in 1941 had published a creative interpretation of Hamlet entitled Shin Hamuretto

(The New Hamlet).

To be, or not to be – that is the question;

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them; to die: to sleep –

No more, and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished – to die: to sleep –

To sleep, perchance to dream – ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil

Must give us pause:

(3.1.55-67)

Tsubouchi’s translation was originally made in 1909 and substantially revised in 1933 (12).

Yo ni aru, yo ni aranu, sore ga gimon ja. Zanninna unmei no

to be in the world – not to be in the world – that is the question – cruel fate –

ya ya ishinage wo, hitasura taeshinonde ore ga danshi no honi ka, aruiwa umi nasu

arrows and slings – entirely – suffer – my male will – or else – like a sea –

kannan wo mukaeutte, tatakaute ne wo tatsu ga daijoubu no kokorozashi ka? Shi wa

adversity – resist – fight – stand firm – alright – will – [interrogative] – death –

… nemuri … ni suginu. Nemutte kokoro no itami ga sari, kono niku ni

sleep – is no more than – sleeping – heart’s pains – disappear – in this flesh –

tsukimatoute ore senbyaku no kurushimi ga nozokaruru mono naraba … sore koso

beset – I – hundred thousand – pains – if they can be escaped – that itself –

ue mo nau negawashii daishuuen jaga. … Shi wa … nemuri … nemuru!

no more – desirable – consummation – there is – death – sleep – to sleep –

Aa, osoraku wa yume wo miyou! … Soko ni sawari ga aru wa. Kono keigai no

oh, perhaps – I will see a dream – in there – is the hindrance – this body’s

wazurai wo kotogotoku datsu shita toki ni, sono samenu nemuri no uchi ni,

troubles – every – cast off – when – that – unwaking – sleep – within –

dono youna yume wo miru yara? Sore ga kokorogakari ja.

what kind of – dreams – to see – that is – my concern

(Tsubouchi 1933: 114-115)

This is a highly poetic translation, rhythmical and euphonious, but one of the inevitable effects of such a poetic translation is that it tends to emphasize Hamlet’s answer above his question. Phrases such as zanninna unmei

(‘outrageous fortune’) and negawashii daishuuen

(‘consummation devoutly to be wished’) stand out against the dramatic trope of a mind in turmoil; likewise, the hushed pauses in Shi wa … nemuri … ni suginu

can even sound melodramatic.

Fukuda, in his post-war translation, is more concise:

Sei ka, shi ka, sore ga gimon da, dochira ga otokorashii ikikata ka,

life or death – that is the question – which is – the more manly – way of living –

jitto mi wo fuse, fuhouna unmei no yanage wo taeshinobu no to,

sticking firmly to the ground – unlawful destiny – slings and arrows – enduring –

sore tomo tsurugi wo totte, oshiyoseru kunan ni tachimukai, todome wo sasu made

or else – taking a sword – pouring in – troubles – face up to – finish off – until –

ato ni wa hikanu no to, ittai dochira ga. Isso shinde shimatta hou ga. Shi wa nemuri

later – not withdrawing – which on earth? – all the better to die – death – sleep –

ni suginu – sore dake no koto de wa nai ka. Nemuri ni ochireba, sono shunkan, issai

no more than – only that thing – isn’t it? – if you fall asleep – that moment – all –

issai ga kiete nakunaru, mune wo itameru urei mo, nikutai ni tsukimatou

will fade to nothing – that will hurt the breast – griefs also – in the flesh – beset –

kazukazu no kurushimi mo. Negatte mo nai saiwai to iu mono. Shinde, nemutte,

countless pains too – beyond hope – something that is fortunate – to die – sleep –

tada sore daka nara? Nemutte, iya, nemureba, yume mo miyou. Sore ga iya da.

if that’s all it is – to sleep – no! – if I sleep – then I will dream – I don’t like that –

Kono sei no keigai kara datsu shite, eien no nemuri ni tsuite, aa, sore kara

from this life’s body – to be parted – eternal sleep – arriving – oh, then –

donna yume ni nayamasareru ka, dare mo sore wo omou to –

by what kind of dreams will I be troubled – anyone – would think that

(Fukuda 1967: 84-85)

What is at once striking about Fukuda’s translation is the focus on Hamlet’s question about the choice of life and death rather than the answer on which he then elaborates. His translation of the long first sentence concludes with a question – ittai dochira ga?

(‘which on earth should I choose?’) – which is absent from the original, but which effectively summarizes the content of that opening sentence for a Japanese audience. Fukuda is even able to make the question sound reflective rather than overly interrogative, using the subject particle ga

rather than the interrogative ka, which renders the sentence incomplete, and in that sense ‘reflective’. Moreover, unlike Tsubouchi, he does not insert dramatic pauses (omoiire

in Tsubouchi’s kabuki terminology) (13) into the lines ‘To die, to sleep. / To sleep, perchance to dream. Ay, there’s the rub’, but instead allows the probing logic of the original to speak for itself. As indicated above, a back translation of Fukuda’s version reads as follows:

to die – to sleep – if that’s all it is – to sleep – no! – if I sleep – then I will dream – I don’t like that

The first real pause in Fukuda’s translation follows Shakespeare’s direction, ‘Must give us pause’: dare mo sore wo omou to (‘anyone would think that’). I have mentioned that Fukuda aims to produce a faster translation than Tsubouchi, but in this excerpt at least Fukuda uses 307 morae against Tsubouchi’s 272. Where Tsubouchi is slower is in his use of dramatic pauses and kanji

compounds, such as zannin

(‘cruelty’) and kantan

(‘adversity’) which tend to disrupt the flow of Japanese words; Tsubouchi uses fifteen kanji compounds against Fukuda’s eight.

Fukuda once declared that 90% of the lyrical beauty of Shakespeare’s poetic language is lost in translation (Kawachi, 93), and although many Japanese readers have found his translations poetic and even beautiful, and the example given here of his style seems to be both rhythmical and lively, it is apparent that the pace is set primarily by Fukuda’s determination to maintain the logic of the line. He brings out that logic by adding explanatory phrases such as tada sore dake nara

and before that sore dake no koto de wa nai ka

(‘is not death more than sleep?’), and most forcefully the phrase Isso shinde shimatta hou ga,

which again is entirely absent from the source but answers Hamlet’s question by saying ‘It would be all the more preferable to die …’. Fukuda’s addition is also a poetic one.

It goes without saying that Fukuda translated Shakespeare at a time when Japan was seeking to revive its economy, and that economic growth in the early post-war era depended partly on technology transfer from foreign partners. The analogy with Fukuda is even more compelling when one considers that, unlike Tsubouchi and the various Shakespeare adaptors of the Meiji era (14) Fukuda sought merely to make the Shakespeare ‘machine’ work efficiently in a culture in need of spiritual restoration (Nanba). Japan’s economic conditions have changed considerably since the 1950s, but Fukuda’s emphasis on pace is echoed by the dromology, or ‘science of speed’, espoused by Paul Virilio in the 1970s. Virilio writes that ‘speed does not solely permit us to move more easily, above all it permits us to see, to hear, to perceive and thus to conceive more intensively the present world’ (qtd. James, 32), and that ‘the truth of phenomena is always limited by the speed of their sudden appearance’ (ibid.). From Fukuda’s dramaturgical viewpoint, speed conditions the realism of performance, whether that be fast or slow, but it was his determination to produce a faster Hamlet in 1955 that extended the parameters of cognitive perception. As for the present age, Virilio contends ‘that contemporary society is reaching a critical point at which further acceleration may soon no longer be possible’ (James, 30). Since Shakespeare performance is basically conditioned by the original texts (even in the case of translation and adaptation), it is difficult to conceive of it becoming reduced to a kind of virtual reality in any language. If, as Virilio worries, ever faster technologies threaten civilization with the virtualization or ‘desertification of lived embodied experience’ (ibid., 43), Shakespeare translation and performance may play a significant role in connecting audiences with a body of lived experience through a medium of acceleration and deceleration that they understand.

Notes

1. Tsubouchi argued that the colloquial, especially Tokyo Japanese of the early 20th century was inadequate to capture the diversity of Shakespeare’s vocabulary and rhetoric, and sought to enrich it with kabuki style and the style of other early modern Japanese writers.

2. Tsubouchi was born in 1859, nine years before the Meiji Restoration, and died in 1935. Throughout his career, he tended to differentiate between the moralistic literature of the Tokugawa era (1603-1868), which he had enjoyed in his youth, and the social and psychological realism of the great Western writers. Shakespeare, in particular, stood out as a writer of quite literally unfathomable creativity and therefore beyond historical analysis. If Shakespeare could not be adequately historicized, then equally his insights could be freely applied to any period of Japanese literary history. Tsubouchi differs in this way from later translators such as Fukuda, who were either dramaturgs or Shakespeare scholars, in that his approach to Shakespeare translation was grounded in the influential literary theory he developed in the 1880s.

3. Strictly speaking, Fukuda is a shingeki

translator, whereas Odashima and Matsuoka are products of the post-shingeki

movement that originated in the radical left-wing politics of the 1960s. Nevertheless, all three have contributed to the obsession with national identity that defines post-war Japan.

4. The Treaty allowed the presence of American military bases in Japanese territory, and was opposed by left-wing student and political organizations.

5. Ibsen exercised a huge influence on Japanese drama, but as with the traditional drama the tendency of shingeki

has been to emphasize external appearances above inner being.

6. All translations of excerpts from Japanese texts in this article are my own.

7. Other intellectuals prominent at that time included the liberal political scientist Maruyama Masao and the left-wing critic and philosopher Yoshimoto Takaaki.

8. Under the pre-war Imperial system of honorifics, the Emperor’s voice was known as the Jewel Voice, and the speech was delivered in the formal, classical Japanese of the court that made it difficult for ordinary Japanese people to understand. Hirohito’s call for ‘a grand peace’ can be said to have paved the way for Japan’s renunciation of the right of belligerence in the 1947 Constitution.

9. The ideology of the national language (kokugo) was developed in the late Meiji era, and was explicitly related to the movement to amalgamate the language’s written and spoken elements (known as genbun icchi) in order to create a modern language capable of unifying the people under the unequivocal sovereignty of the Emperor (Lee, 53), whose role was for example manifested by his silent presence at meetings of the privy council.

10. The tendency of Japanese to generate words by compounding morphemes, particularly Sino-Japanese characters (kanji).

11. Tsubouchi’s theory of drama, although not the most influential in pre-war Japan, was based primarily on the actor’s voice and the practice of public reading.

12. It was the original 1909 version that was used for Tsubouchi’s production of Hamlet for the Bungei Kyokai at the Imperial Theatre in 1911. Fukuda’s production in 1955 for the Bungakuza was to some extent meant to supplant the precedent set in 1911, which was the first complete theatrical production of a Shakespeare play in Japan done in translation rather than in adapted format. My back translations of the two excerpts that follow use the Japanese word order and ignore the particles (the topic marker wa, subject marker ga, object marker wo, and genitive no).

13. Theatrical pauses in kabuki used by individual actors for emotional effect.

14. Shakespeare adaptations of the Meiji era typically gave the characters Japanese names and used Japanese settings. In the prologues he wrote for his series of Shakespeare translations, Tsubouchi frequently points out correspondences with Japanese drama and culture in a way that is uncommon in post-war translations.

References

Akutagawa Hiroshi, ‘Juriasu Shiza honyakusha ni kiku’ (Interview with the translator of Julius Caesar), in Fukuda (2012), 149-164.

Anzai Tetsuo, Peter Milward, and Ono Hiroshi, ‘Nihon no Sheikusupia · honyaku to joen’ (Shakespeare translation and performance in Japan), in Fukuda (2012), 217-241.

Fukuda Tsuneari, trans. (1967) Hamuretto

(Hamlet), Tokyo: Shinchosha.

––––– (1988) ‘Sheikusupia geki no serifu’ (The Shakespearean line) (1977), in Fukuda Tsuneari zenshu

(Collected Works of Fukuda Tsuneari), Vol. 7, Tokyo: Bungei Shunju, 337-365.

––––– (2012) Fukuda Tsuneari taidan

(Conversations with Fukuda Tsuneari), Vol. 6, Tokyo: Tamagawa University Press.

James, Ian (2007) Paul Virilio, London: Routledge.

Kawachi Yoshiko (1995) Shakespeare and Cultural Exchange, Tokyo: Seibido.

Kawai Shoichiro (2010) ‘Yukio Ninagawa’, in John Russell Brown, ed., The Routledge Companion to Directors’ Shakespeare, London: Routledge, 269-283.

Lee, Yeonsuk (2010) The Ideology of Kokugo: Nationalizing Language in Modern Japan

(‘Kokugo’ to iu shiso), trans. Maki Hirano Hubbard, Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Murata Ganshi, ‘Sheikusupia no serifu to tatakatte’ (Struggling with Shakespeare’s language), in Fukuda (2012), 371-385.

Nanba Takio (1989) ‘Fukuda Tsuneari to Sheikusupia’ (Fukuda Tsuneari and Shakespeare), in Anzai Tetsuo, ed., Nihon no Sheikusupia hyakunen

(A Hundred Years of Shakespeare in Japan), Tokyo: Arakawa Shuppan, 85-132.

Thompson, Ann, and Neil Taylor, ed. (2006) The Arden Shakespeare: Hamlet, London: Cengage Learning.

Tsubouchi Shoyo, trans. (1933) Hamuretto

(Hamlet), Tokyo: Chuo Koronsha.