TEACHING SHEIKUSUPIA

The teaching of Shakespeare in Japanese universities dates back to the formation of a modern system of higher education in the late 19th century. Shakespeare (‘Sheikusupia’ in Japanese pronunciation) was received from the start as a universal genius, a myth that was sustained through the contribution of academic translators such as Tsubouchi Shoyo in the early 20th century, although as a foreign rather than a native Japanese writer.(1) Even if Shakespeare’s cultural assumptions could not be readily applied to the recipient culture, the plays have long provided a means of experiencing universality in a Japanese context.

In this regard, the way that Shakespeare has been received in Japan is perhaps not dissimilar to how the plays have been received anywhere else. Almost all of Shakespeare’s plays are ‘translations’ of existing narratives, and so Shakespeare’s reception in Japan is merely continuing this process of ‘translation’. Even in Anglophone countries, teachers must to some extent use translation as a tool for reading Shakespeare’s early modern English, but translation is obviously rather more central to the teaching of Shakespeare in Japan, where the English language per se is still to some extent taught by the grammar-translation method. I also learnt my French and German that way at British schools in the 1970s and 80s, and it was not until I came to Japan in 1987 that I encountered the communicative methodology of language teaching, the idea that languages are best learnt through the acquisition of communicative skills with little formal grammatical input and rote learning, especially not the repeated correction of errors. At that time, there was a popular view that while educated Japanese people could read English, they lacked the skills and confidence to communicate in English with native speakers. Despite my somewhat limited training, it was the communicative approach that I applied to my role as an Assistant English Teacher on the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Programme,(2) and this approach continues to inform my teaching at a large private university in western Japan. More to the point, and aside from the invaluable MA programme in Japanese Studies I did at Sheffield University in the early 1990s, most of my Japanese has been acquired through the communicative approach of cultural immersion and interaction.

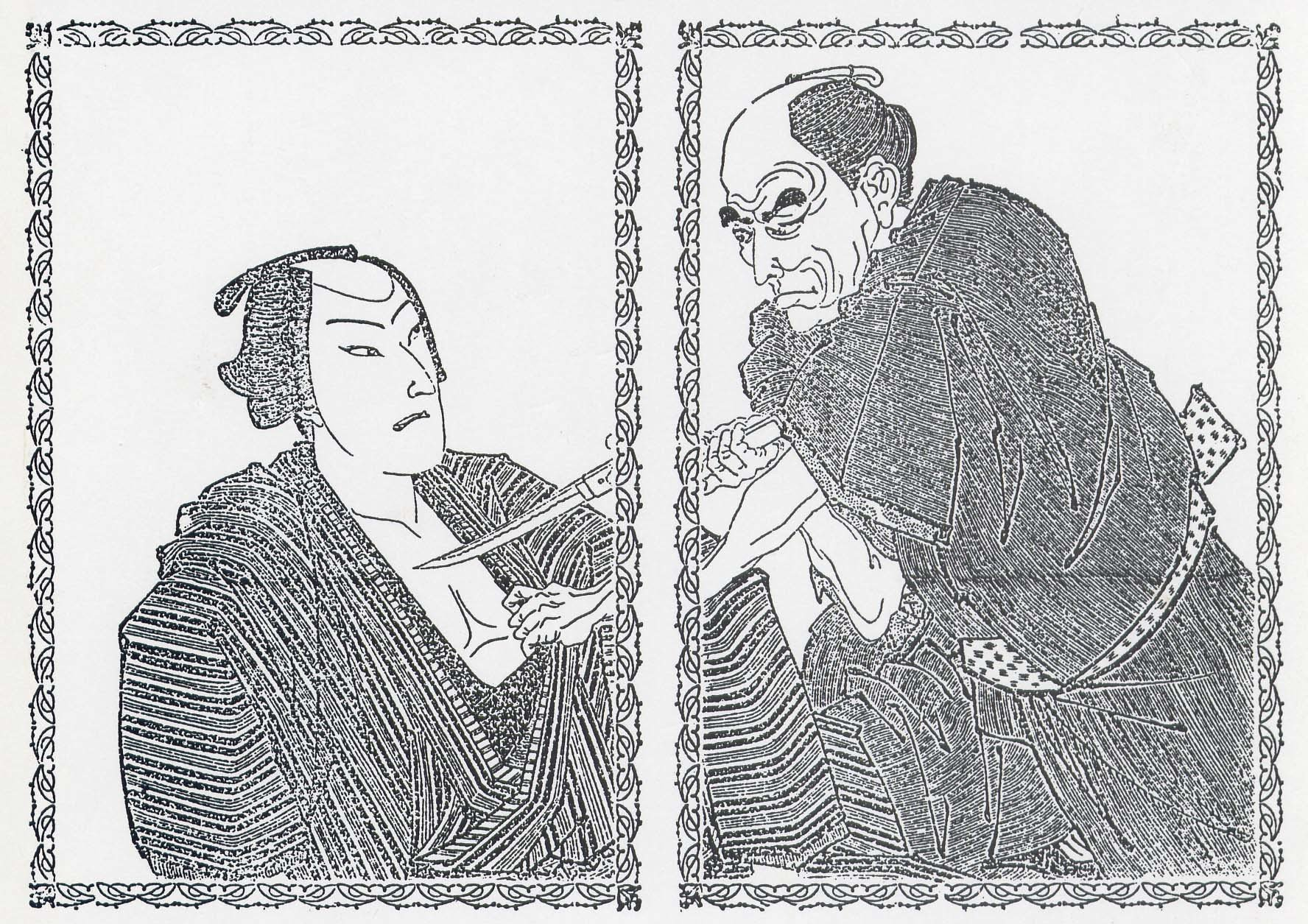

Since returning to Japan in 2003, I have had the opportunity to teach Shakespeare at postgraduate level, and since 2008 have been teaching Shakespeare to undergraduate classes, using the illustrated manga versions published by SelfMadeHero. Between 2008 and 2011 at Japan Women’s University in Tokyo, I taught the manga Hamlet

for three consecutive years, finding that each year’s teaching raised only more questions to be solved; at Kwansei Gakuin University since 2011, I have taught two seminar courses on Hamlet

criticism, and the plot continues to thicken.

The tutorial system at Kwansei Gakuin has also enabled me to teach a broad selection of the plays to 3rd and 4th year undergraduates in the manga versions (in order of tutorial group): Much Ado About Nothing

and, in the spring semester of the 4th year, Romeo and Juliet

(2011-13), A Midsummer Night’s Dream

and As You Like It

(2012-14), Richard III

and Julius Caesar

(2013-15), The Merchant of Venice

and Macbeth

(2014-16), Othello

and Henry VIII

(2015-17), The Tempest

(2016-18), and Hamlet

and, for a second time, Romeo and Juliet

(2017-18). The two plays I have not yet taught in the SelfMadeHero series are King Lear

and Twelfth Night, and so these are planned for my next two tutorial groups in 2020 and 2021. In 2017, I followed up The Tempest

with a contemporary play, Timberlake Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good

(1988), since both plays have a strong postcolonial interest, and plan to continue this format in future, and when I taught Hamlet

in 2017-8 used the 2008 Cliff’s Notes edition, which has more of the original text than the SelfMadeHero publication.

In teaching Shakespeare to Japanese students, I am faced with a practical problem that may also be related to a deeper cultural issue of what Shakespeare means to Japanese people. To start with, I always try to create a communicative classroom environment in which (as I tell the students) the main language is English, and yet somehow inevitably end up using far more Japanese than intended. The manga editions, through their cutting of the original text by as much as 80% and use of graphic images to illustrate dramatic situations and plot development, aid teachers and learners in developing a shared understanding of the plays, and have the particular strength of retaining Shakespeare’s original text in the fifth that remains. To take one familiar example, Hamlet’s fourth soliloquy is reduced to the following bite-sized chunks (Vieceli amd Appignanesi 2008, 78-79):

To be or not to be … that is the question.

To die, to sleep, to sleep, perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub …

The dread of something after death puzzles the will.

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all.

Sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, enterprises lose the name of action.

Three words in this excerpt are displayed in bold type – ‘cowards’, ‘lose’ and ‘action’ – suggesting that the unambiguous message of the soliloquy is that cowards fail to act. In fact, the graphic nature of the manga genre lends itself to such stark interpretations; at the end of the Julius Caesar

(Mustashrik and Appignanesi 2008, 205), Brutus is presented in the giant figure of a crucified martyr to replace the image on the cover of Caesar in the same posture against an ominous Roman skyline. Other typical effects include doubling faces to reveal mixed feelings and reducing characters to child size when they are acting childishly; these devices, like Shakespeare’s own rhetoric, all serve to tell the story and to open up the plays to interpretation

Manga is of course familiar to Japanese students as a genre for both children and adults, and I have to say that my initial fears that students would not take it seriously as a medium for studying ‘a serious writer’ like Shakespeare have never been reciprocated. Yet for all its advantage as a teaching tool, manga Shakespeare still leaves a lot to be explained. In the 3rd year, it takes me twenty weeks out of the two fourteen-week spring and autumn semesters to read a whole play, including the time spent on role play activities, watching a film version, and historical background, and this time gives the students the reading skills to tackle a whole play in the spring semester of the 4th year before writing their graduation dissertations (sotsuron), the ultimate goal of all undergraduate degree courses in Japan. In the Hamlet

excerpt, the following words and phrases demand explanation: ‘perchance’ (perhaps), ‘the rub’, ‘puzzles the will’, the connection between conscience and cowardice, ‘sicklied’ and ‘cast’, and the final metaphor is also tricky. Elsewhere, the stuff about purgatory and hell can certainly take up time with students unfamiliar with such concepts, even leading to the impression that Hamlet

is primarily a religious play, although both the manga format and numerous film versions tend to dispel that impression. Moreover, in language-centred teaching, the focus will be predominantly on Shakespeare’s metaphors, offering as they do to students the greatest challenges and the greatest rewards: Shakespeare’s ‘universality’ is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in his metaphorical comparisons of like with unlike, and (I would argue) is experienced most intensely through the cognitive effort required to understand the metaphors.

In order to gauge students’ own response to the translingual Shakespeare classroom, I recently conducted a brief survey, asking them to grade their level of agreement to five statements as follows:

① strongly disagree ② disagree a little ③ agree ④ agree a lot ⑤ strongly agree

1. There is a satisfactory balance of English and Japanese used in the classroom.

① 0 ② 1 ③ 9 ④ 8 ⑤ 5

2. I would like more opportunities to speak English in the classroom.

① 0 ② 2 ③ 10 ④ 6 ⑤ 5

3. I can understand the text of the manga Shakespeare without the teacher’s explanation in Japanese.

① 4 ② 13 ③ 2 ④ 3 ⑤ 1

4. I can understand the text of the manga Shakespeare after hearing the teacher’s explanation in Japanese.

① 0 ② 0 ③ 4 ④ 13 ⑤ 6

5. The teacher’s Japanese is difficult to understand.

① 4 ② 15 ③ 4 ④ 0 ⑤ 0

These figures suggest that while the Shakespeare is getting through loud and clear, certainly more could be done to create an interactive classroom. Out of three students who provided ‘further comments’, one wrote that ‘It’s really hard for me to understand Shakespeare’s original English, but I think it’s very worthwhile me trying [to do so]’. The two others praised what they called in Japanese my polite (teinei) style of teaching. Teinei

is an ambiguous label, but what I would want it to mean is a classroom in which students do not feel objectified by either the text or my teaching: one, in other words, in which there is no pressure to be Ophelia, Beatrice or Shylock, and where they feel free to grow alongside the texts they are reading. As a teacher, I no doubt tend to underestimate their understanding, and so at the very least would like to give a full thirty of the ninety minutes’ class time to task-directed small group activities in which rather than having to understand every detail, students can read and discuss the texts together in English. Japanese students are eminently capable of understanding Shakespeare; I would like them to talk about Shakespeare as well.

References

1. Kishi and Bradshaw compare the possessive claim of 19th century German critics to ‘unser [our] Shakespeare’ with Japanese people for whom ‘Shakespeare is always foreign’ (Kishi and Bradshaw, 27).

2. In addition to JET training seminars, I was particularly inspired by Krashen and Terrell’s classic study of language acquisition, The Natural Approach

(1983).

Kishi, Tetsuo and Graham Bradshaw. Shakespeare in Japan. London: Continuum. 2005.

Krashen, Stephen D. and Tracy D. Terrell. The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom. Oxford: Pergamon Press. 1983.

Mustashrik, and Richard Appignanesi. Manga Shakespeare: Julius Caesar. London: SelfMadeHero. 2008.

Vieceli, Emma, and Richard Appignanesi. Manga Shakespeare: Hamlet. London: SelfMadeHero. 2008.